You must be signed in to read the rest of this article.

Registration on CDEWorld is free. You may also login to CDEWorld with your DentalAegis.com account.

The appropriate treatment for external cervical resorption (ECR) is dependent on the severity of the disease's progression-namely, the spread, accessibility, and prognosis of the resorptive lesion. That being said, ECR poses substantial diagnostic and treatment planning challenges, even for highly experienced clinicians.1-3 However, the provision of appropriate treatment is necessary because the resorption can result in a large, irreversible loss of dental hard tissue.4 The objective of ECR treatment is to eliminate the resorptive tissue and seal the portal of entry with an esthetic, biocompatible material to prevent recurrence.2

Evidence-supported treatment modalities for ECR include external (ie, surgical) repair, internal repair, extraction, and active monitoring as well as novel treatment methods, such as intentional replantation and orthodontic extrusion. Although the selection of the appropriate modality to manage ECR is largely dependent on the stage of disease progression and accessibility of the lesion,5 there are case selection concerns for each treatment modality that should be considered.

External Repair

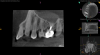

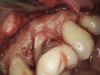

If an ECR lesion is surgically accessible, external repair with gingival flap surgery is the treatment of choice (Figure 1 through Figure 6). When considering external repair, clinicians should evaluate each case for potential postoperative esthetic concerns, such as the possibility of recession following surgical repair.6,7 Moreover, clinicians should assess the overall restorability of affected teeth because the surgical repair of large ECR lesions may predispose them to fracture.6 When a Heithersay Class 1 lesion is diagnosed, nonsurgical root canal therapy (NSRCT) in addition to the surgical repair is often unnecessary. However, in Heithersay Class 2 or larger defects where pulpal involvement is suspected or confirmed, NSRCT may be necessary in addition to surgical repair.6 If NSRCT is indicated in addition to surgical repair, it is recommended that it be completed prior to surgery to avoid exacerbating pulpal disease.

The surgical repair of ECR lesions is relatively straightforward. First, a sulcular incision should be created to develop a full-thickness flap that allows for complete visualization of the resorptive defect. Subsequently, all of the resorptive tissue should be removed. Curette instrument options for resorptive tissue removal may include appropriately sized excavators, scalers, or a diamond bur in a high-speed handpiece. Next, the resorptive cavity should be cleaned, and any areas of thin dentin that prevent access to the depth of the lesion should be removed with a high-speed bur or an ultrasonic scaler. If the margin of the resorptive defect sits at the crestal bone, judicious removal of the crestal bone via crown lengthening may be necessary to avoid biologic width violation.6

Once prepared, the resorptive cavity should be treated topically with a 90% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solution. TCA serves to eliminate any remaining clastic cells, which are known to tunnel through the dentin beyond the visible cavity margins.5 Because TCA is quite caustic, to avoid injury, care must be taken to prevent it from accidentally being applied to the bone or soft tissue.8 Place a small amount of TCA in a small glass dappen dish and apply it to the resorptive lesion with a large absorbent paper point or small cotton pellet.5 TCA causes coagulation necrosis of any residual resorption tissue; however, this effect is nonspecific, so it is crucial to apply it carefully because it can cause chemical burns to the oral mucosa or skin.8

After TCA treatment, the resorptive cavity should be restored with a biocompatible restorative material that does not wash out in saliva or gingival crevicular fluid. Due to this latter requirement, resin-modified glass ionomers are often more appropriate restorative materials in these cases than other bioceramic materials.8,9 Once restored, the patient should be recalled for follow-up appointments at 6 months and at 1 year postoperatively, at a minimum, to assess the progress of healing and for any recurrent resorption.5

Internal Repair

Not all ECR cases are surgically accessible. In cases in which an infrabony defect is inaccessible or in which surgically accessing an ECR defect would result in excessive removal of sound tooth structure, internal repair is the treatment option of choice (Figure 7 through Figure 11).5 The internal approach requires access to the ECR defect through the root canal system; therefore, NSRCT must be performed prior to its initiation. After cleaning and shaping the root canal, the ECR lesion is accessed by violating the predentin with long shank burs and endodontic ultrasonic tips. Any visible resorptive tissue should be removed mechanically, with care taken to avoid extrusion of sodium hypochlorite, or any irrigant, through the resorptive portal into the periodontal ligament to prevent an accident.5

The resorptive lesion should then be treated with a topical application of 90% TCA solution. Just as during the external approach, care must be taken during TCA application due to its caustic properties. A small amount of TCA should be placed in a small glass dappen dish and applied to the resorptive lesion with a large absorbent paper point.8 After TCA application, the resorptive defect is restored.11 Unlike during external repair, where the washout of materials is a concern due to their exposure to the oral cavity, internally repaired ECR lesions are often best restored with bioceramic materials, which have demonstrated documented success when placed next to periodontal ligament structures.12-14 Bioactive, biocompatible calcium silicate-based restorative cements (eg, Biodentine®, Septodont; EndoSequence® BC RRM-Putty™, Brasseler USA; MTA-Fillapex, Angelus) have been proposed as possible repair materials for resorptive lesions.12-15 It is believed that the calcium ions released from such cements creates an alkaline environment suitable for osteoblastic activity and stimulates the release of factors favorable for mineralization.10 Mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) has also been used in the sealing of ECR defects.13 This biocompatible material has been shown to stimulate mineralization and demonstrates antibacterial activity and good sealing ability, allowing it to create an ideal environment for hard tissue healing.12 In addition, MTA has been shown to induce repair of the periodontium and the formation of new cementum.13

Extraction

Extraction is considered the best treatment alternative for cases of ECR in which traditional treatments come with a poor prognosis because the teeth exhibit other symptoms or pathologic bone loss. Moreover, certain patients may simply prefer extraction to other treatment alternatives due to their past experiences, economics, or intolerance to risk. Whenever extraction is considered, comprehensive treatment planning should include a discussion of future replacement options so that plans and procedures can account for the patient's needs and desires.5,16

Active Monitoring

If an ECR lesion is inaccessible externally or internally, and it is neither symptomatic nor associated with pathologic bone loss, active monitoring represents a reasonable treatment alternative. This is frequently the treatment of choice for patients presenting with Heithersay Class 4 ECR defects or truly inaccessible Class 2 or Class 3 defects. Annual reevaluation is recommended for these patients, and the use of cone-beam computed tomography (CBCT) imaging should be considered.5,16

Novel Treatment Methods

Although external repair and internal repair represent the most common treatment modalities for ECR, intentional replantation has been proposed as a novel treatment method.5,17 Research recommends this treatment for lesions that are inaccessible surgically or internally. The treatment protocol requires NSRCT to be completed first. The tooth is then atraumatically extracted, and the lesion is debrided, treated with TCA, and restored with a bioceramic material. Replantation of the tooth in its original socket should take place within 15 minutes to allow for complete healing of the periradicular tissues. Following replantation, the tooth should be splinted with a flexible splint for 2 weeks. Orthodontic extrusion can provide another novel approach to treating inaccessible ECR lesions; however, a discussion of this complex methodology is beyond the scope of this article.17

Treatment Prognosis

In a tooth with ECR, the size of the resorptive lesion and the amount of remaining intact tooth structure have a significant influence on treatment prognosis.2 Unsuccessful treatment is associated with continued progression of the resorptive lesion and suboptimal restoration integrity.18 Heithersay found that, using the methods presented in this article, the treatment of Class 1 and Class 2 ECR lesions resulted in a 100% success rate, the treatment of Class 3 ECR lesions resulted in a 77.8% success rate, and the treatment of Class 4 ECR lesions resulted in a 12.5% success rate.19 Early identification and treatment of ECR can help prevent lesions from becoming more extensive and inaccessible, which leads to poorer prognoses.5 ECR lesions have been found to demonstrate a nonlinear increase in volume over time, going through remineralization phases and resorption phases. However, these defects have been shown to ultimately increase in volume over time, which suggests that delaying treatment may worsen the prognosis of teeth with ECR. Further research is necessary to assess the long-term outcomes of treatment in teeth with ECR.20

Conclusion

ECR is a common form of external root resorption that can remain asymptomatic with limited clinical features, rendering its diagnosis difficult and often resulting in misdiagnosis. Treatment modalities exist that can halt disease progression, particularly when lesions are diagnosed and treated early.21 The selection of the most appropriate treatment modality depends on the size and accessibility of the lesion, among other factors. Discerning clinicians should recognize that there are differing approaches to the management of ECR and that careful diagnosis and treatment planning is imperative to ensure positive outcomes.

Queries regarding this course may be submitted to authorqueries@broadcastmed.com

About the Authors

Alice Li, DMD

Resident

Harvard University

School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Brooke Blicher, DMD

Assistant Clinical Professor

Department of Endodontics

Tufts University

School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Lecturer

Department of Restorative

Dentistry and Biomaterials

Science

Harvard University

School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Rebekah Lucier Pryles, DMD

Assistant Clinical Professor

Department of Endodontics

Tufts University

School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Lecturer

Department of Restorative

Dentistry and Biomaterials

Science

Harvard University

School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

Jarshen Lin, DDS

Instructor

Department of Restorative

Dentistry and Biomaterials

Science

Harvard University

School of Dental Medicine

Boston, Massachusetts

References

1. Patel S, Kanagasingam S, Pitt Ford T. External cervical resorption: a review. J Endod.2009;35(5):616-625.

2. Chen Y, Huang Y, Deng X. A review of external cervical resorption. J Endod. 2021;47(6):883-894.

3. Heithersay GS. Invasive cervical resorption. Endod Topics. 2004;7(1):73-92.

4. Bergmans L, Van Cleynenbreugel J, Verbeken E, et al. Cervical external root resorption in vital teeth. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29(6):580-585.

5. Patel S, Mavridou AM, Lambrechts P, Saberi N. External cervical resorption-part 1: histopathology, distribution and presentation. Int Endod J. 2018;51(11):1205-1223.

6. Patel S, Foschi F, Condon R, et al. External cervical resorption: part 2-management. Int Endod J. 2018;51(11):1224-1238.

7. Heithersay G. Management of tooth resorption. Aust Dent J. 2007;52(1 Suppl):S105-S121.

8. Glogau RG, Matarasso SL. Chemical peels. Trichloroacetic acid and phenol. Dermatol Clin. 1995;13(2):263-276.

9. Rajawat A, Kaushik M. Stresses in teeth with external cervical resorption defects restored with different biomimetic cements: a finite element analysis. J Endod. 2023;49(8):995-1003.

10. Baranwal A. Management of external invasive cervical resorption of tooth with Biodentine: a case report. J Conserv Dent. 2016;19(3):296.

11. Rotondi O, Waldon P, Kim SG. The disease process, diagnosis and treatment of invasive cervical resorption: a review. Dent J (Basel). 2020;8(3):64.

12. Kqiku L, Ebeleseder KA, Glockner K. Treatment of invasive cervical resorption with sandwich technique using mineral trioxide aggregate: a case report. Oper Dent.2012;37(1):98-106.

13. Ikhar A, Thakur N, Patel A, et al. Management of external invasive cervical resorption tooth with mineral trioxide aggregate: a case report. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:139801.

14. Shemesh A, Ben Itzhak J, Solomonov M. Minimally invasive treatment of class 4 invasive cervical resorption with internal approach: a case series. J Endod. 2017;43(11):1901-1908.

15. Asgary S, Nosrat A. Conservative management of class 4 invasive cervical root resorption using calcium-enriched mixture cement. J Endod. 2016;42(8):1291-1294.

16. Patel S, Kanagasingam S, Pitt Ford T. External cervical resorption: a review. J Endod. 2009;35(5):616-625.

17. Rotondi O, Waldon P, Kim SG. The disease process, diagnosis and treatment of invasive cervical resorption: a review. Dent J (Basel). 2020;8(3):64.

18. Jebril A, Aljamani S, Jarad F. The surgical management of external cervical resorption: a retrospective observational study of treatment outcomes and classifications. J Endod. 2020;46(6):778-785.

19. Heithersay GS. Treatment of invasive cervical resorption: an analysis of results using topical application of trichloracetic acid, curettage, and restoration. Quintessence Int. 1999;30(2):96-110.

20. Irinakis E, Haapasalo M, Shen Y, Aleksejuniene J. External cervical resorption - treatment outcomes and determinants: a retrospective cohort study with up to 10 years of follow-up. Int Endod J. 2022;55(5):441-452.

21. Patel J, Beddis HP. How to assess and manage external cervical resorption. Br Dent J. 2019;227(8):695-701.